Water discovered in the Great Red Spot indicates Jupiter might have plenty more

CLEMSON, South Carolina — On Dec. 7, 1995, NASA’s historic Galileo probe plunged into Jupiter’s atmosphere at 106,000 mph, relaying 58 minutes of data back to Earth before it was pulverized in the depths of the enormous planet’s crushing interior.

In terms of atmospheric composition, some of what the probe measured met expectations. But there were also some surprises, one of the most baffling being that the region Galileo entered was drier than astrophysicists had anticipated. Jupiter’s 79 moons are mostly made of ice, so it had been assumed that the planet’s atmosphere would contain a considerable amount of water. If so, the 750-pound probe didn’t find it that day.

Almost a quarter of a century later, experts are still debating how much water might be swirling within Jupiter’s howling atmosphere. Recent research by a national team of scientists – including Clemson University astrophysicist Máté Ádámkovics – indicates that the answer is … a lot.

“By formulating and analyzing data obtained using ground-based telescopes, our team has detected the chemical signatures of water deep beneath the surface of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot,” said Ádámkovics, an assistant professor in the College of Science’s department of physics and astronomy. “Jupiter is a gas giant that contains more than twice the mass of all of our other planets combined. And though 99 percent of Jupiter’s atmosphere is composed of hydrogen and helium, even solar fractions of water on a planet this massive would add up to a lot of water – many times more water than we have here on Earth.”

Ádámkovics’ collaborative research was recently featured in Astronomical Journal, one of the world’s premier journals for astronomy. He was part of a team that included Gordon L. Bjoraker of NASA; Michael H. Wong and Imke de Pater of the University of California, Berkeley; Tilak Hewagama of the University of Maryland; and Glenn Orton of the California Institute of Technology. The paper was titled “The Gas Composition and Deep Cloud Structure of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.”

The team focused its sights on the Great Red Spot, a hurricane-like storm more than twice as wide as Earth that has been blustering in Jupiter’s skies for more than 150 years. The team searched for water by using radiation data collected by two instruments on ground-based telescopes: iSHELL on the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility and the Near Infrared Spectograph on the Keck 2 telescope, both of which are located on the remote summit of Maunakea in Hawaii. iShell is a high-resolution instrument that can detect a wide range of gases across the color spectrum. Keck 2 is the most sensitive infrared telescope on Earth.

The team found evidence of three cloud layers in the Great Red Spot, with the deepest cloud layer at 5-7 bars. A bar is a metric unit of pressure that approximates the average atmospheric pressure on Earth at sea level. Altitude on Jupiter is measured in bars because the planet doesn’t have an Earth-like surface from which to measure elevation. At about 5-7 bars – or about 100 miles below the cloud tops – is where the scientists believed the temperature would reach the freezing point for water. The deepest of the three cloud layers identified by the team was believed to be composed of frozen water.

“The discovery of water on Jupiter using our technique is important in many ways. Our current study focused on the red spot, but future projects will be able to estimate how much water exists on the entire planet,” Ádámkovics said. “Water may play a critical role in Jupiter’s dynamic weather patterns, so this will help advance our understanding of what makes the planet’s atmosphere so turbulent. And, finally, where there’s the potential for liquid water, the possibility of life cannot be completely ruled out. So, though it appears very unlikely, life on Jupiter is not beyond the range of our imaginations.”

Clemson’s main role in the research was to use specially designed software to transform raw data into science-quality data that could be more easily analyzed and also shared with scientists at Clemson and around the world. This type of work was performed this past spring by Rachel Conway, an undergraduate student in physics and astronomy who became involved in the project via Clemson’s Creative Inquiry program.

“When I initially began, I started by running the data through. The code was already written and I was just plugging in new data sets and generating output files,” said Conway, a native of Watertown, Connecticut. “But then I began fixing errors and learning more about what was actually going on. I’m interested in everything and anything that’s out there, so learning more about what we don’t know is always cool.”

A team of Creative Inquiry undergraduate researchers will assist Ádámkovics (far left) on the next Jupiter project.

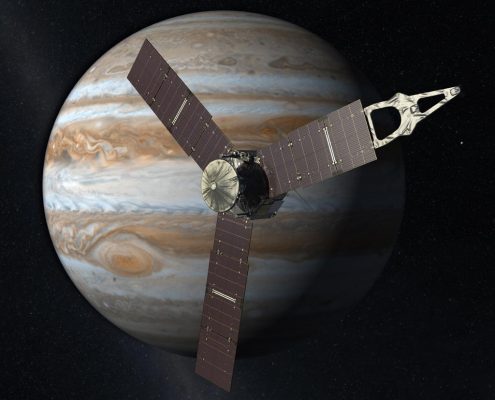

NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which arrived at Jupiter in 2016 and will be orbiting and studying the planet until at least 2021, has revealed many secrets about a planet so large it almost became a star. Juno is also searching for water by using its own high-tech infrared spectrometer. If Juno’s observations match ground-based observations, then the latter can be applied not just to the Great Red Spot, but to all of Jupiter. The technique als0 can be used to study Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, our solar system’s three other gas planets.

“Starting this fall, the next project will be to get a lot more data of this kind to measure not just one spot on Jupiter. but all over Jupiter,” said Ádámkovics, whose research focus is on the physics and chemistry of planet formation, planetary atmospheres and circumstellar disks. “To do this, we’ll be collecting many gigabytes of data with the new instrument, iSHELL, that works at a very high resolution and will complement Juno’s observations. The new part of this next project will be to write the automated software for all this data so that we can get a full picture of the planet’s water abundance.”

This time around, Ádámkovics and Conway will have some new members on their Clemson team. Ádámkovics will add six to eight Creative Inquiry students to assist with analyzing the raw data.

“In addition to physics students, we also have students who are computer scientists and who specialize in other fields,” Ádámkovics said. “We expect that these cross-disciplinary skill sets will complement each other by enhancing our effectiveness and efficiency. Jupiter still has many mysteries. But we’ve never been more ready or more able to solve them.”