Mixed-reality simulation provides practical classroom experience for College of Education students—minus the classroom

For students on the path to a career in education, it can be hard to beat the experience gained during a classroom field experience working with real students. However, faculty and students in the Clemson University College of Education’s special education program are proving that sharpening teaching skills in a virtual world complete with virtual student avatars has its place and is becoming increasingly effective in teacher preparation.

A research team comprised of faculty, graduate students and undergraduate students is studying the effectiveness of mixed-reality simulation as an aid for undergraduate students studying to become special education teachers.

According to Sharon Walters, a doctoral student leading a team of undergraduate researchers in the study, the research is showing that this form of instruction is an effective complement to—or in some cases, a substitute for—practical classroom experience with students with intellectual disabilities, those with emotional or behavioral disorders, or potentially any student at any grade level.

“I see it as a bridge that we’ve never really had before that exists between classroom-based educator preparation and student teaching or field placements,” Walters said. “Engaging with students, especially students with special needs, is always the most effective form of practice, but there are things that mixed-reality simulation can provide that could never exist in a peer-to-peer, college classroom setting.”

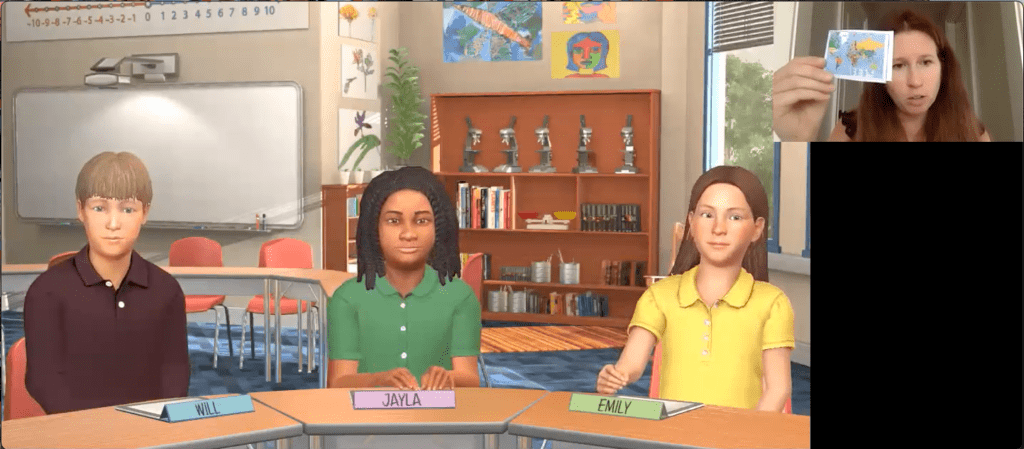

Mixed-reality simulation allows Clemson students to engage with virtual student avatars over Zoom. The avatars are digital students with unique personalities. The experience is provided by The AVATAR Lab (supported by Mursion) at Kennesaw State University, with whom the college has contracted to explore the effectiveness of mixed-reality simulation.

“It’s like gaining muscle memory for an educator; it becomes automatic, which in turn makes them more comfortable when they eventually reach the classroom. If they’ve responded appropriately to enough difficult situations in simulation, it helps to ensure they can manage a classroom appropriately when they’re faced with the real thing.”

SHARON WALTERS

During past simulations, Clemson students lead classroom activities with one or more avatars, which gives them the opportunity to practice academic instruction or classroom management skills with a group or in one-on-one interactions with students with special needs. This semester Clemson special education student teachers will use the simulator to practice skills such as organizing and facilitating effective meetings with professionals and families.

Shanna Hirsch, assistant professor in the college who is researching the effectiveness of mixed-reality simulation, received funding more than two years ago from Clemson’s Office of Academic Affairs and Provost to run the simulator and take advantage of the service provided by Kennesaw State. Hirsch had previously used simulations during her Ph.D. studies at the University of Virginia, so she had already seen the technology’s potential to provide Clemson students with practical classroom experiences online.

“It’s fortuitous that this process was in motion before COVID-19 hit, because obviously this has been very effective in providing remote learning for our students,” Hirsch said. “But for me, simulation allows me to observe and provide almost immediate feedback to dozens of students in a short window of time. That would be impossible in practical classroom settings as our students are typically placed across a number of schools.”

What students have to say

“The mixed-reality simulation allowed me to gain confidence, and I was able to practice my direct instruction skills before entering the classroom.”

-Rylie Beasley, Junior

“I went into the experience fearful that it may not sufficiently provide realistic teaching experiences, but the simulator surprised me. It truly did feel as if I were speaking to students right in front of me.”

-Emma Allen, Senior

“When you are teaching a relatively easy lesson it can be easy to breeze through material, but the simulator allowed me to focus on the basic elements of teaching such as checking in on students and really gaining their attention.”

-Katlyn Goad, Junior

Hirsch and Walters have conducted research on the effectiveness of simulation versus traditional classroom practice for students learning to use the system of least prompts, a procedure that promotes learning of skills by children with and without disabilities. Walters’ doctoral dissertation is focused on the use of mixed-reality simulation to implement a clarifying vocabulary technique with students with language impairments. Student avatars display behaviors consistent with language impairment, and Clemson students will use the simulation to learn how to support them.

Both projects have included undergraduate students via Clemson Creative Inquiry, a University-wide program that engages students in research activities on a variety of topics. Walters said these undergraduate researchers have been instrumental in designing and running the study as well as scoring and presenting results. Students involved in the research presented findings at the South Carolina Council for Exceptional Children conference in 2020.

The projects as well as student feedback suggest that simulation is both an effective complement to teaching and something college students enjoy using. Walters said the practice with an avatar lends the experience a much more realistic quality compared to peer-to-peer practice, and avatars can respond in ways that students don’t expect, which “keeps them on their toes.”

From an instructor’s point of view, Walters said simulation allows her to use the same scenario with an entire class, which allows her to make instruction delivery conform to a standard. The opportunity for students to repeat a simulation is also valuable for basic practice on a situation or concept with which they may be struggling.

“It’s like gaining muscle memory for an educator; it becomes automatic, which in turn makes them more comfortable when they eventually reach the classroom,” Walters said. “If they’ve responded appropriately to enough difficult situations in simulation, it helps to ensure they can manage a classroom appropriately when they’re faced with the real thing.”

Hirsch said that currently a small number of universities use the technology, but she feels that will change as the technology improves, faculty and staff realize its benefits and best practices are developed in its use. The research that she, Walters, Dr. Catherine Griffith and Creative Inquiry students have conducted is going a long way in establishing those best practices, so Hirsch feels that the college as a whole is uniquely positioned to factor simulation into instruction in a variety of ways.

“The special education faculty have supported its continued use and evaluation,” Hirsch said. “It’s exciting to use an emerging technology such as this, but even more so when we’re potentially setting the stage for its use by other faculty and students not only in the college but in the field of education.”