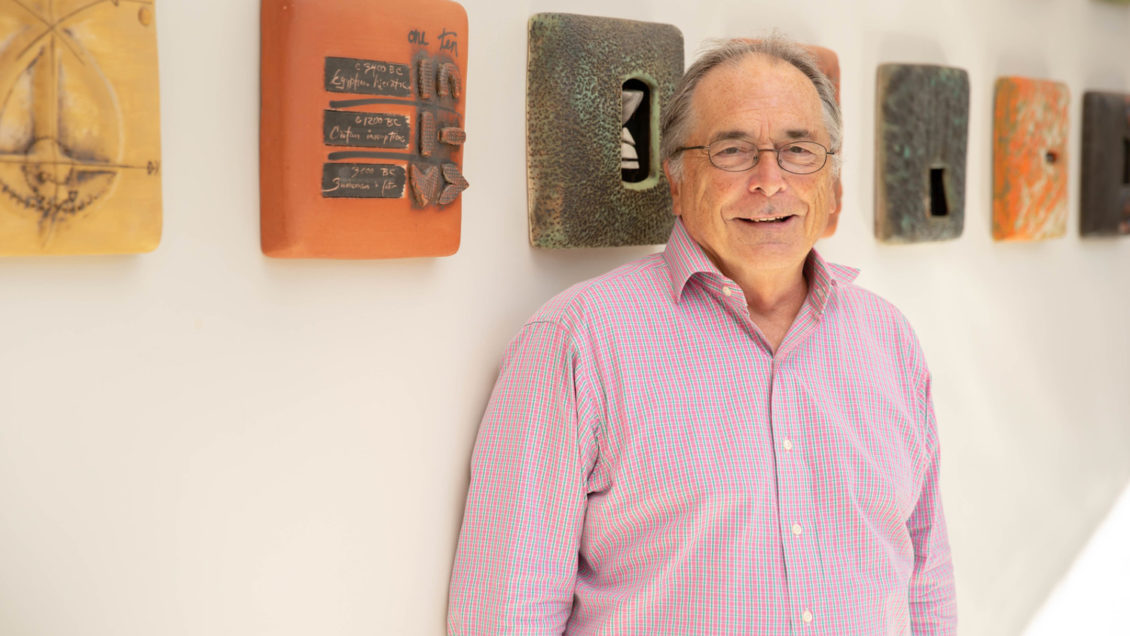

History professor Alan Grubb recalls his career and Clemson through the decades

Alan Grubb vividly recalls a time before the iconic Clemson University Tiger Paw was born.

In 1967, when Grubb first arrive on campus, the student population was one-third the size it is today. Few women attended the University. Orange didn’t dominate the landscape.

And all the freshmen wore rat caps.

Grubb is celebrating 51 years of teaching history at Clemson. Dozens of past and present students and faculty saluted Grubb during an annual history alumni gathering at Hardin Hall in September. Grubb regaled the crowd with anecdotes from his career.

Grubb is the longest-serving current professor on campus, and in that time he’s seen a good state college evolve into a nationally ranked university.

When Grubb arrived at Clemson, the Vietnam conflict was raging, no one had stepped foot on the moon, and the Beatles were still together.

Grubb, 24 years old at the time, walked into Hardin Hall for an interview in February 1967. He began teaching that August and has spent his entire teaching career in Hardin, the oldest building on campus.

Grubb never imagined he’d be at Clemson more than a few years.

“A lot of us came here and we weren’t married,” Grubb said. “Clemson was not the greatest place to be a bachelor. Most of the faculty were married. It was a common statement among young professors, ‘We won’t be here very long.’”

That was a half century ago.

“Alan has been a mentor to three generations of Clemson students,” said James Burns, chair of the Clemson Department of History. “He has always been incredibly selfless with his time, whether it be in his exhaustive editing of graduate student theses, or in the hours of time he spends with students in office hours.”

Grubb teaches a variety of undergraduate and graduate courses on European intellectual history, World War I, Modern France and The Age of Absolutism.

When Grubb was hired to teach history, the Department of History didn’t exist. The Department of Social Sciences encompassed history, political science, psychology, sociology, and philosophy and religion.

For professors, less emphasis was placed on research and more on teaching. Grubb said he taught five classes every semester for several years, including some courses on Saturday. “Now, it would take armed police to get professors to teach on Saturday,” he said.

Another memory stands out to Grubb. Many buildings on campus lacked air conditioning and could get stuffy on hot days. “Air conditioning was the godsend for the South. It changed everything,” he said.

Tiger passion for football

Grubb has seen a lot of changes across campus, but the Tiger passion for football has been a constant – even if traditions were different in 1967.

“There wasn’t tailgating back then,” he said. “The closest thing to it is that people came and picnicked around Clemson House. But people did have parties, and they dressed up!

“Historians talk about tradition a lot but most traditions are actually pretty new,” he added. “All the things you think have been around forever are recently invented.”

Grubb remembers Old South traditions being replaced by new and more inclusive ones in the 1960s and ’70s.

“There was no Tiger Paw flag,” Grubb said. “There was a ‘Dixie’ flag. That disappeared in the 1970s. There were some protests about the (Confederate) flag, and it went away, which was kind of neat. There was also a guy, sort of a mascot, who went around as a Southern gentleman. He disappeared, too.”

Clemson had become a co-educational, civilian college only 12 years before Grubb’s arrival. Its military origins were still evident in 1967, Grubb said.

“We had one of the largest ROTC programs in the country,” Grubb said. “We turned out a lot of officers in the Vietnam War. The military tradition was fading but it was still pretty strong.”

At the time, 6,305 undergraduates attended Clemson, according to the 1967 undergraduate catalog. Now, 19,402 undergraduates attend Clemson.

Women made up a small portion of the student body in 1967, and they most often majored in education, Grubb said.

Many of the young people attending Clemson at the time were first-generation college students. “Students were not well-prepared but they were determined and they struggled and improved a lot,” Grubb said. “They had trouble writing but they worked hard, and they got better. They had a strong work ethic. Today’s students are much better prepared.”

Grubb witnessed a building boom in his first few years. Strode Tower was completed in 1969. Cooper Library had just been dedicated in 1966. “These were the new, modern buildings,” he said.

Choosing Clemson

Grubb was born in Washington, where his father owned the oldest pharmacy.

Growing up in the nation’s capital, a city steeped in the past, inspired Grubb to study history. “Most of my youth, I was aiming to be a lawyer, but being around so many historical sites brought me to history,” he said. “Washington, D.C. was kind of a small, Southern town. I delivered prescriptions to the Supreme Court, to Congress, to the Library of Congress. It was very small world. Now it’s a pricey world.”

Grubb studied pre-law, then English but eventually earned his undergraduate degree in history at Washington and Lee University. He earned his master’s degree and Ph.D. in history from Columbia University, when he received teaching offers from Clemson and a university in California.

“I decided that I was an East Coast person rather than a West Coast person,” Grubb said. “Clemson appealed to me more than the other schools where I was a candidate.”

Grubb lived in a faculty apartment behind Clemson House, the famous hotel and later residence hall, for 10 years. After getting married, he moved to the house in Clemson where he has lived since 1977.

“I could always walk to Clemson,” Grubb said. “I especially walked here when my kids were in high school because they always had my car.”

Advocate for history

Today, Grubb retains his abiding passion for history and is a strong advocate for the value of a history degree.

A humanities education offers the communication and critical thinking skills employers want to see in today’s graduates, Grubb said. “You learn a lot about a lot of things and you have an ability to exchange ideas,” he said. “That’s adaptable for many things – for instance, teaching, the law and business.”

In his courses, Grubb often assigns popular history texts – such as the works of Pulitzer Prize-winning Barbara Tuchman — rather than academic histories. “Good popular historians keep history alive,” Grubb said. “So many historians are good writers.”

Grubb also combats what he perceives as a decline in reading by requiring full texts in his courses. “I use whole books. I don’t use parts of books and most often don’t use anthologies,” he said. “I think there’s something to be said for just finishing a book.”

Among his own history projects, Grubb has recently started a Creative Inquiry program to collect memories of Clemson House, built in 1950 and demolished in 2017. Creative Inquiry courses at Clemson allow small, faculty-led teams of undergraduate students to research a variety of topics. Grubb’s group plans to publish its research and photos in a book.

“It’s going to basically focus on people’s recollections,” Grubb said. “It was once known as the smartest hotel in the Carolinas. It was famous. People drove from all around to eat there, particularly on Sundays.”

After 51 years of teaching, Grubb has no plans to retire.

The students keep him going, he said, particularly the occasional ones who discover a new love for history.

“I find the classroom exciting,” he said. “I’ve had students who say they hated history but by the end of the semester they come to love it. It’s exciting when you make connections like that. You don’t set out to make converts, but there are people who write me years later and tell me they remember my lectures.

“I don’t even remember my lectures sometimes,” he added with a laugh. “But they remember them.”