Data from the Dead

by Tessa Schwarze

When there was a grave robbery at a Pickens County cemetery, the coroner called Dr. Katherine Weisensee in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Criminal Justice to come and investigate. Weisensee, who specializes in forensic anthropology, said that the coroner had another favor to ask in addition to the investigation. The county had a room full of death records dating back to 1970 and the coroner wanted to know if students wanted to organize them. Weisensee accepted and the Death in Pickens County Creative Inquiry project began.

When there was a grave robbery at a Pickens County cemetery, the coroner called Dr. Katherine Weisensee in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Criminal Justice to come and investigate. Weisensee, who specializes in forensic anthropology, said that the coroner had another favor to ask in addition to the investigation. The county had a room full of death records dating back to 1970 and the coroner wanted to know if students wanted to organize them. Weisensee accepted and the Death in Pickens County Creative Inquiry project began.

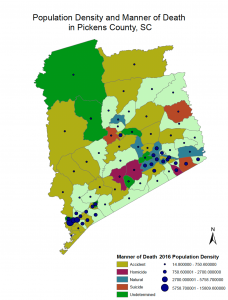

The goals of the project are more than basic organizational tasks. They use Geographic Information System (GIS) software in their record keeping, which allows them to digitally store the records and look at it spatially. Every death has a geolocation which allows the students to overlay other information with the same geolocation, including data about socioeconomic status and population density. Using GIS allows them to look at relationships between the deaths and other data to better understand patterns of deaths occurring in Pickens County. The database is a goldmine: a data treasure trove, uncommon in rural areas.

Only a few such databases exist, and all of them are from urban centers outside of the Southeast. However, instead of merging the database with the rest of the United States, the project isolates Pickens County as a singular research population. The team is almost exclusively looking at what is unique about death here.

Their analyses are uncovering some interesting discoveries, particularly regarding cases of suicide. It is commonly reported in the literature that females frequently choose non-violent means of suicide, such as drug overdose. However, in Pickens County, the vast majority of female suicides are gun related. Although suicide is currently a focus of the team, many of the death records list heart failure or car accidents as the cause of death. These numbers can be extremely helpful for health intervention and population education. “Because these data are down to the census block, we can really make specific inferences about Pickens, not just [general] health and violence. By examining patterns of death across space and over time you can understand the living population,” Weisensee says.

The team has entered more than 1,000 records in the database, but there are thousands remaining. Christina Martinson, a senior anthropology major, notes that data entry can be a draining process, but the benefits are worth it. Skills in database development and management as well as GIS software are highly marketable skills giving these students a competitive advantage after graduation. “Our research database asks about the person in detail and most of these details are missing from the original records, so we work as a team to systematically input,” Martinson says.

The data does not die in Pickens County. The students are able to attend the annual American Academy of Forensic Sciences Conference to disseminate their findings and to learn more about the discipline. “This project is what anthropology is all about—the community. This benefits the students, it benefits the county, and benefits the sciences by building this database about [a population] we can learn more about life and death in our area,” Weisensee says.